HOW TO HELP STUDENTS AVOID THE REMEDIAL EDUCATION TRAP

No question, remedial education needs an overhaul. Millions of young adults get trapped in rudimentary math and English classes that don’t earn them college credits but still cost the same tuition. More than two-thirds of all community college students and 40 percent of undergraduates in four-year colleges have to start with at least one developmental education class, in the euphemistic jargon of higher education. The majority of these students drop out without degrees.

Some college systems are trying to change those statistics. California State University is eliminating its remedial classes and putting all of its freshmen in college-level courses this fall. Remedial classes have been optional in Florida since 2014. Many other colleges are reducing the number of students who are sent to remedial coursework by changing the rules that funnel students into these prerequisite classes.

But many educators have doubts about whether skipping remedial classes altogether is a wise idea for students who failed to master subjects in high school. One idea gaining popularity is something called “corequisites.” The idea is that students take two classes at once, one remedial and one that earns college credit. But there’s very little research to show that this approach works. One of the few corequisite programs to be studied is an “Accelerated Learning Program” at the Community College of Baltimore County, where the same instructor taught both the remedial and college material to classes limited to 10 students.

Such small classes are not feasible for large institutions with many thousands of students. Texas, Tennessee, and Virginia are quickly rolling out less expensive corequisite variations. Last week, researchers at the RAND Corporation published a report offering an early glimpse into the problems facing Texas community colleges, from faculty resistance to the lack of new corequisite textbooks or teaching materials.

The researchers are currently running an experiment in which they randomly assigned some Texas community colleges students to a corequisite model with an extra hour of remedial instruction added to a college-level English class. The full results won’t be known until 2021 after the researchers follow these students and see if their graduation rates improve. But even before the final report, a new Texas law is requiring that three-quarters of all developmental ed students enroll in corequisites by 2020.

“We weren’t planning to issue a report, but states are scaling this up so quickly,” said RAND policy researcher Lindsay Daugherty, one of five authors on the report. “We’ve been collecting all this implementation data and we thought we’d publish it so that others can avoid the challenges that Texas colleges have run into.”

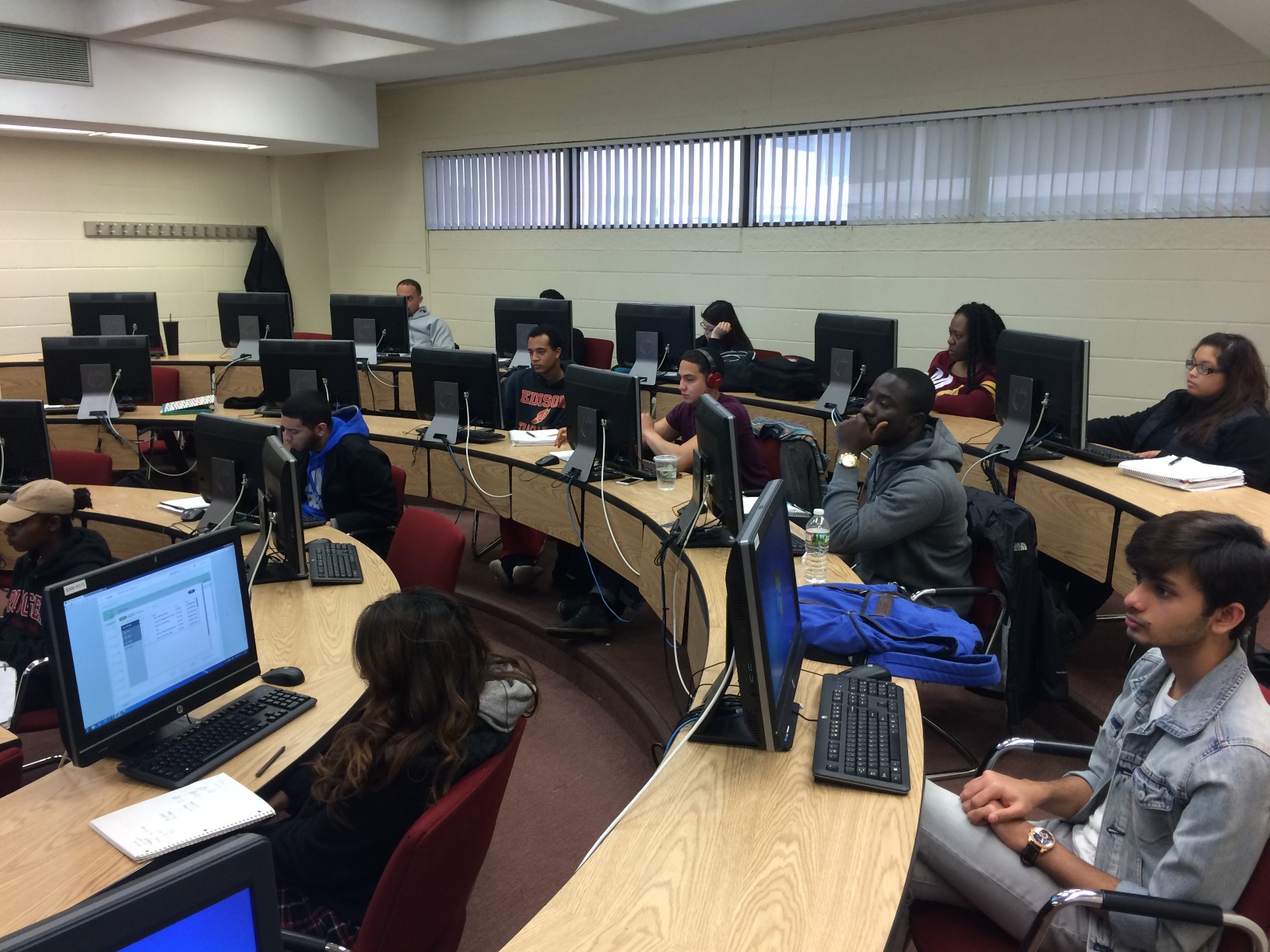

Daugherty’s first observation is that Texas community college administrators have quickly created more than 35 different flavors of corequisite programs. Some colleges are simply making students enroll in two separate classes, taught by two different instructors, without making any changes to the curriculum or the schedule. Another approach adds instructional time to the college-level course, increasing class time to four hours a week from three. Others are adding mandatory tutoring, instructor office hours or time in a computer lab using instructional software.

The term corequisite can sometimes mean any type of support that struggling students are given to get through a college-level class. By that definition, even Cal State’s plan to abolish remedial classes could be considered a corequisite model when it provides extra help to students.

Daugherty is seeing more promise in some models, less in others.

The easiest model for colleges to implement is requiring students to enroll in two English (or math) classes simultaneously instead of sequentially. Colleges don’t have to restructure anything and there’s no coordination between the two classes.

“Some colleges are taking what exists and try to make it work,” said Daugherty. “There are limited prospects for success. The colleges that start from scratch and really focus on what the student needs to succeed in the college level course are more promising.”

Daugherty argues that the remedial curriculum needs to be completely rewritten, targeted to what the student is learning each week in the college course. Instead of giving students disconnected grammar exercises and quizzes, Daugherty says, the grammar should be taught in the context of what the students are reading and writing in the college-level course.

Some of the stiffest resistance to corequisite models comes from developmental education instructors, Daugherty says. They’re not qualified to teach college-level courses and they feel under attack. The threat of job cuts looms. Daugherty says college administrators need to take more time before implementing a change to explain to developmental education instructors why students will benefit.

Daugherty is intrigued with models that eliminate the remedial classroom altogether. One college in El Paso requires students to go to office hours once a week. In Dallas, students must sign in at a writing center once a week and work with tutors. A problem for colleges is that they can’t charge students tuition for these services and they can charge tuition for a remedial class. Texas enacted changes to its funding formula so that community colleges could get paid for the extra office hours and tutoring but that might not be possible in other states.

The RAND researchers are starting to see early evidence that some of these corequisite models are working for students who arrived at college just below the academic threshold needed to enter college-level classes. Texas colleges are now expanding their co-requisite programs to students who are far less prepared. And it remains an open question whether these struggling students will be able to pass college classes with a little corequisite help.

Corequisites may sound like a great solution on paper, helping kids catch up while they are earning college credit. But instructors and students are still left with the hard work of teaching and learning. It’s going to take time to figure out how to do it right. Policymakers should not push colleges to put thousands of struggling students through a new ill-defined corequisite model before we know if it works and, if it does, for which students.

Jill Barshay

Jill Barshay

Jill Barshay is a contributing editor who writes the weekly “Proof Points” column about education research and data. She taught algebra to ninth graders for… See Archive