In rural Maine, a university eliminates most F's in an effort to increase graduation rates

The University of Maine at Presque Isle hopes new approach will produce more skilled workers for a struggling region.

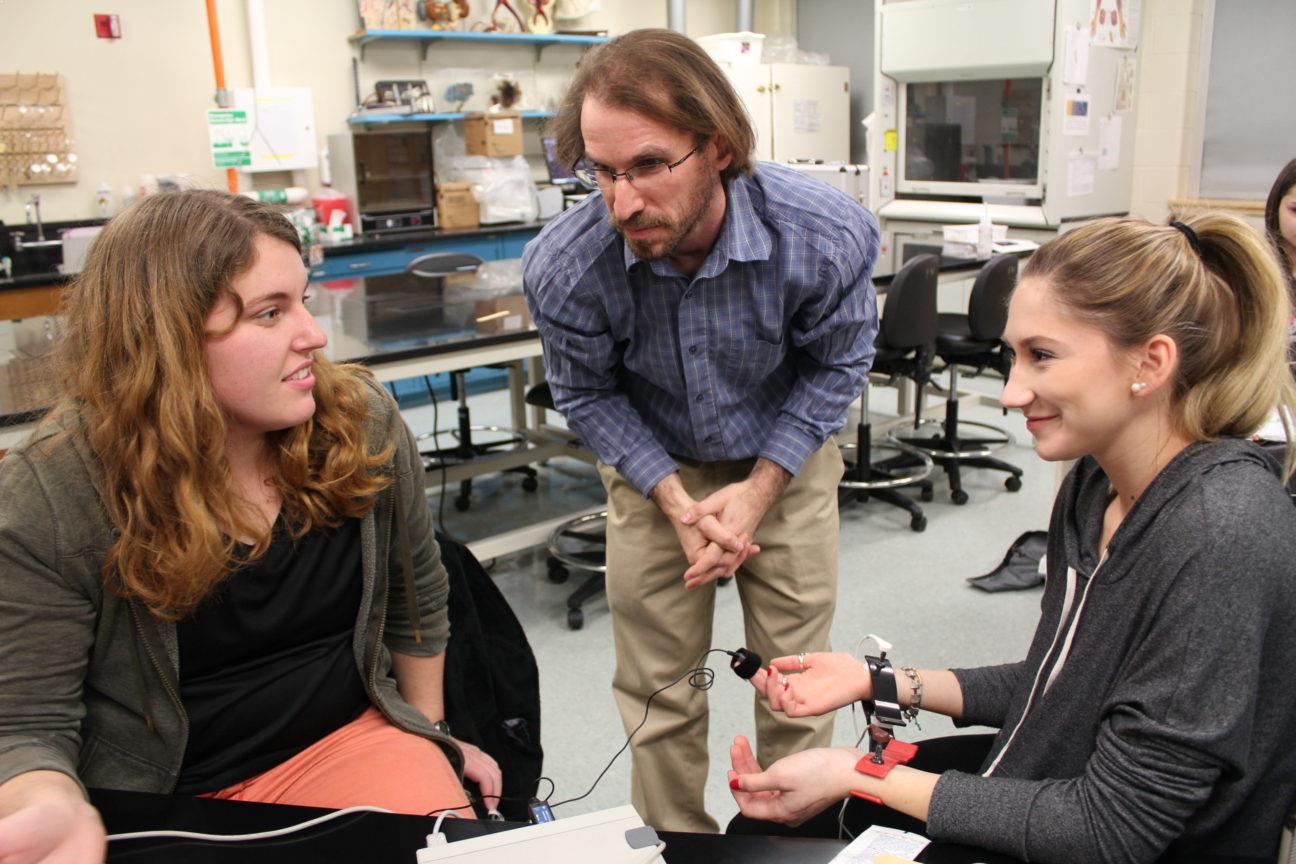

RESQUE ISLE, Maine — For the first few minutes of Scott Dobrin’s anatomy and physiology class at the University of Maine at Presque Isle, nothing feels particularly out of the ordinary. Dobrin lectures on blood clots and vessels, mapping out diagrams on a whiteboard.

But after about half-an-hour, the lecture stops and Dobrin presents his students with a menu of options.

“Is anyone interested in taking an assessment today?” Dobrin asks. He then mills around the room, meeting with students individually or in small groups. Some students fill out a handout or watch a video online. Others take tests first given two or three weeks ago. It’s an open work time — full of choices — that Dobrin says he never would have offered five years ago.

This change is part of a larger move at the university towards “proficiency-based education” (sometimes called competency- or mastery-based education). In the traditional model, students need to pass a specific set of courses to graduate. But in a proficiency-based system, students must show that they’ve mastered “competencies” — specific skills or knowledge — before they move on to the next level, and eventually receive a diploma.

States across New England have adopted similar approaches at the K-12 level. Five years ago, Maine adopted a law requiring every high schooler to show proficiency in up to eight content areas in order to graduate. But the University of Maine at Presque Isle (or UMPI) is one of the first public universities in the nation to use proficiency-based learning.

With the new initiative, university officials are betting on this new, still unproven, form of education, hoping to improve their institution and upgrade Northern Maine’s workforce.

But the obstacles ahead are substantial. Only 11 percent of the students who entered UMPI in 2005 graduated in four years, and only 30 percent graduated in six — all at a time when the region desperately needs more college grads. The university is located in Maine’s rural Aroostook County, just a stone’s throw from the Canadian border. The county has lost nearly a tenth of its population over the past 15 years as paper mills and a local Air Force base have closed.

UMPI President Raymond Rice says many of the jobs that remain, in fields like agriculture and forestry, require an associate’s or bachelor’s degree. “We don’t have the success we need to see for getting students into the workforce,” Rice said. “And in order to improve the economy here, we’ve got to get students to completion.”

One of the biggest changes has been the near-elimination of the failing grade. In most classes, if students fail a test or project, they can redo it until they’ve proven they know the material.

If students are still failing at the end of the semester, many won’t receive an F, but instead a grade of “not proficient” or NP. Under the system, students then sign a contract with their professor outlining the work they need to do over the next 45 days to boost that grade to a passing mark. University officials said the system doesn’t work for everyone; some students still end up with F’s. But they hope the added flexibility will help students pass classes the first time so they don’t have to spend extra time and money to retake them.

For senior Allison Lopez, those additional supports meant she could take her time on concepts that were especially difficult, like a unit in biology class on the endocrine system.

Junior Alex DesRuisseaux and senior Jesus Garcia work in the library of the University of Maine at Presque Isle.

“You can take it at your own pace,” said Lopez, who made the dean’s list last June. “It gives me time to really work and understand it, instead of being forced to get through it and just basically try to remember things to pass a test or pass a paper in.”

“I know I’m smart enough to get that passing grade,” Lopez added. “It’s not like it’s not there. It is there; I just haven’t had a chance to show it yet. And once I did get a chance to show [the professor] that, I did come out with the proficiency I wanted to.”

Vanessa Pearson, UMPI’s interim dean of students, says as part of the shift, professors and administrators have also examined their own courses to identify “learning outcomes,” which are specific pieces of knowledge that students must know to graduate from a certain program.

As an example, Pearson offers a course in the criminal justice program. One of the learning outcomes for Policing in the Community might be “to understand the laws regarding domestic violence,” Pearson said.

Five years ago, students needed to know those laws, but in a more abstract way — memorizing the material and taking a test on it, Pearson said. Now, the focus is on how to apply that knowledge; coursework includes case studies or interviews with lawyers and advocates for domestic abuse survivors, she added.

“It’s making us intentional about what are we teaching, why are we teaching it, what value does it serve,” Pearson said, “so students don’t end up with a bunch of courses that don’t relate to what they want to do.”

Other colleges, particularly private, online degree programs at institutions like Western Governors University, have designed competency-based education programs, but most are aimed at adult students. Lindsay Daugherty, a policy researcher with the nonprofit RAND Corporation, warns that the model could be more difficult for younger students.

“Where they’re going from sitting in a high school class to being completely self-managing, 100 percent responsible with less structure, it is a big change,” Daugherty said. “And it takes a lot of support from those institutions. Having someone side-by-side with these students, keeping them on track. Academic support. Tutoring.”

UMPI officials said that the institution’s limited class sizes — about one staff member for every 15 students — helps to provide that support.

But some students say the system can reward procrastination. Student Matthew Amnott said during his early classes, he’d routinely see students slack off and wait to study until the day of a test. Then, after a few redo’s, they’d boost their grade to an 80 or 90.

“And I don’t think that’s fair to students who put in the work ahead of time, got a 95, took the test one time, as opposed to a student who took a test three times and was able to get a similar or close score,” Amnott said.

Students Matthew Amnott and Brittany Parmelee work on a group project inside a physical therapy class at the University of Maine at Presque Isle.

Another unexpected challenge to changing student attitudes is the unevenness of the implementation of proficiency-based education in high schools across Maine and New England. While some school districts have embraced the new reforms, others have resisted. And researchers at the University of Southern Maine found that educators in some schools haven’t had much success with some of the new instructional strategies.

That’s meant that for some students, like junior Alex DesRuisseaux, their first experience with proficiency-based education wasn’t necessarily positive. DesRuisseaux, a junior education major at UMPI, said that when she attended high school in southern New Hampshire, her school had only just begun implementing reforms in its math department. DesRuisseaux said for her, that change meant laziness — not better learning.

“Because what it meant for me is, you got assigned math homework every night and it wasn’t graded,” DesRuisseaux said. “It was like, ‘Oh, free pass! I don’t have to do anything.”

Wendi Malenfant, a professor of education at UMPI, said she’s heard similar stories from incoming students. “Some [students] feel like it worked really well, and that’s why they came here,” Malenfant said. “But others were pretty discouraged about it.”

The university is still in the early stages of implementing the reforms, but officials are optimistic that it’s making a difference. According to data provided by the university, the school’s first-to-second year retention rate started to rise in 2015. But last year, the retention rate fell to 58 percent, below the national average.

Still, President Raymond Rice said he’s most encouraged that about 60 percent of students who received a “not proficient” grade eventually converted it to a passing mark.

“That, alone, is something that’s been really good for students,” Rice said. “Instead of grades that cost them in terms of time to completion and financials.”

And student DesRuisseaux said her experiences at UMPI have changed her attitude. DesRuisseaux is taking risks on projects and assignments, particularly those in her education classes, because she knows she can redo them later on if she tries something and it doesn’t work out.

“Learning how to transition from being assigned work into seeking out your own work is a very different thing,” DesRuisseaux said. “But once you find what you’re passionate about, it’s so much better. It just takes a little bit of time.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

Robbie Feinberg

Robbie Feinberg

Robbie Feinberg is the education reporter with Maine Public Radio, where he covers everything from childcare to adult education.