Most colleges enroll many students who aren’t prepared for higher education

At more than 200 campuses, more than half of incoming students must take remedial courses

BALTIMORE — The vast majority of public two- and four-year colleges report enrolling students – more than half a million of them–who are not ready for college-level work, a Hechinger Report investigation of 44 states has found.

The numbers reveal a glaring gap in the nation’s education system: A high school diploma, no matter how recently earned, doesn’t guarantee that students are prepared for college courses. Higher education institutions across the country are forced to spend time, money and energy to solve this disconnect. They must determine who’s not ready for college and attempt to get those students up to speed as quickly as possible or risk losing them altogether.

Most schools place students in what are called remedial courses in math or English before they can move on to a full load of college-level, credit-bearing courses – a process that is a financial drain on not only students but also colleges and taxpayers, costing up to an estimated $7 billion a year.

At least 569,751 students were enrolled in remedial classes that year. The true total is likely much higher because of inconsistencies in the way states track this data that may not capture adults returning to school or part-time students.

The rates are “so high that there’s no question students are getting out of high school without the skills they need to succeed in college,” said Alex Mayer, a senior research associate at MRDC, an education and social policy research organization. “The other side of it is these students are not getting out of college, for the most part.”

Indeed, research has shown that students who enroll in these remedial courses often never even make it into the classes that will count toward a degree. A similarly wide-ranging 2012 report by Complete College America determined that nearly half of entering students at two-year schools and a fifth at four-year schools were placed in remedial classes in the fall of 2006. Nearly 40 percent of students at two-year schools and a quarter of those at four-year schools failed to complete their remedial classes, that report found.

Different states use different cutoff scores to determine who must take these classes, which makes remediation-rate comparisons difficult and, critics say, remedial placement somewhat arbitrary. But despite the difficulty of comparison, many states have strikingly high remediation rates in their public colleges and universities.

One of those is Maryland. At many public schools in the state, it’s uncommon for an incoming student not to be placed in remedial education. At Baltimore City Community College, for instance, in the fall of 2015, only 13 percent of students were deemed ready to start on college-level math and English courses right away, according to data provided by the school.

All BCCC students must take a test in math and English called the Accuplacer upon enrolling. The standardized test is one of two used by most higher education institutions to determine students’ readiness. (Some schools use high school GPA or scores on the SAT or ACT.)

At BCCC, and many other institutions, students are placed into one of three levels of remedial courses based on their test scores. (Starting in the summer of 2017, BCCC will only have two levels of remedial math.) A student at the bottom level in math might need help with basic arithmetic. A student who places into the lowest-level English course might still struggle with something as elementary as subject-verb agreement, said Melvin Brooks, associate dean of English, Humanities, Visual and Performing Arts at BCCC.

“Some of them are so deficient, to try to include them in a credit-bearing course without that foundation would be a disservice,” he said, adding that the professor and other students would also be held back by a classmate ill-equipped to keep up.

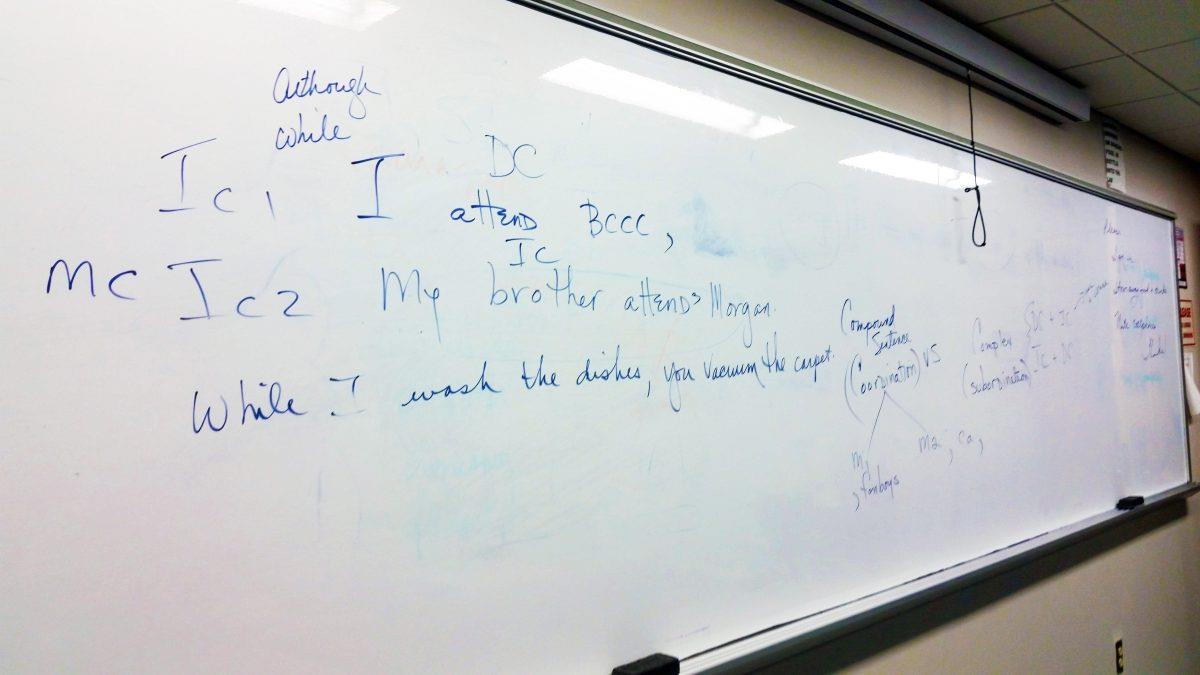

Carole Quine teaches the highest-level remedial English course at BCCC. It focuses predominantly on essay writing. On a Wednesday last fall, she started off her class with a now-routine exercise: diagramming a sentence. She then wrote two sentences on the board — “I attend BCCC” and “My brother attends Morgan” — and had students suggest different ways of combining them. (One student jokingly suggested, “I attend BCCC because my brother attends Morgan.”)

“The major reason you’re being taught all this is when you get into your English 101, you aren’t just writing the same kinds of sentences,” Quine told them.

Sitting in the back of the class, Gregory Scott Peterson took notes as Quine went over the difference between dependent and independent clauses.

Peterson graduated from high school in 2015 and enrolled at BCCC in the fall of 2016 through a program that will earn him a certificate in Information Technology followed by a six-month internship that should turn into a full-time job.

Peterson placed directly into Quine’s class, without needing the lower two levels of remediation. Still, he said, for the first few weeks he and many of his classmates were “on the struggle bus.”

He said that the class was “definitely a lot harder” than his high school English courses.

Remediation is sometimes assumed to be primarily driven by adults returning to college, who may have once understood the quadratic formula and mastered the five-paragraph essay but have forgotten them in the intervening years. The data collected by The Hechinger Report indicate, however, that the problem is widespread among students coming directly from high school as well.

In Nevada, for instance, 58 percent of the state’s recent high school graduates were placed in these courses in 2014. And more than half of Delaware’s recent public high school graduates who enrolled in its public colleges and universities needed remediation that year.

Maryland has reported similarly high remediation rates for its high school graduates. A study of the Baltimore City Public Schools class of 2011 found that 96 percent of the 354 students who immediately enrolled at BCCC needed remedial courses in math and 67 percent needed remedial courses in writing. At the Community College of Baltimore County, where 417 of the 2011 graduates ended up, 89 percent tested into remedial math classes and 49 percent into remedial writing. (Several four-year schools had lower rates, but these two colleges received over 60 percent of Baltimore graduates attending Maryland public institutions.)

Sonja Brookins Santelises, chief executive officer of Baltimore City Public Schools, is well aware of the gap between the knowledge needed to earn a diploma in the district and what college professors expect students to be able to do on day one. She served as chief academic officer for the district before going to the D.C.-based think tank Education Trust in 2013, where she studied this issue nationally. She returned to the Baltimore school district in the summer of 2016.

Sonja Brookins Santelises, chief executive officer of Baltimore City Public Schools, is well aware of the gap between the knowledge needed to earn a diploma in the district and what college professors expect students to be able to do on day one. She served as chief academic officer for the district before going to the D.C.-based think tank Education Trust in 2013, where she studied this issue nationally. She returned to the Baltimore school district in the summer of 2016.

It’s “more like a chasm,” she said. “We’ve had too low a standard for too long.”

The district is working to increase dual-enrollment opportunities, through which high school students can enroll in college courses, as well as increase general exposure to higher education, Santelises said. It’s also trying to equip schools with the tools to deal with trauma in students’ lives and to better support teachers in raising standards to challenge students more in high school.

“If we’ve been giving kids worksheets with simplistic answers for years and then get upset when they can’t write a five-paragraph essay or recognize subject-verb agreement, that’s not the kids,” she said. “That’s us.”

Santelises said she thinks the district should be able to cut the remediation rate of Baltimore City graduates going to BCCC or the Community College of Baltimore County in half over the next four years.

To significantly decrease remediation rates takes time.

Hechinger’s analysis shows that remediation rates have been declining in most states over the last five years, yet often those drops have been small, even as states adopted new K-12 standards aimed at aligning high school graduation requirements and college-readiness standards. No one has completely bridged the gap, said David Steiner, executive director of the Institute for Education Policy at Johns Hopkins University and a former commissioner of education for New York State.

“No state right now is close to equating its high school graduation standard with anything that would be meaningful as a college-career-starting standard,” he said. But, Steiner added, the problem is magnified in communities like Baltimore. “The fact also is that when you get concentrated high poverty, it’s extremely hard to educate the student out of that situation to college readiness.”

Indeed, many colleges with high remediation rates say that they have accepted that not all — often not even most — of their students will be completely ready when they come to campus.

“You have to work with what you get,” said Sandra Kurtinitis, president of the Community College of Baltimore County. “We get honors students and folks who can’t read at a fifth-grade level.”

“You have to work with what you get,” said Sandra Kurtinitis, president of the Community College of Baltimore County. “We get honors students and folks who can’t read at a fifth-grade level.”

In general, according to Hechinger’s data analysis, remediation rates are higher at community colleges, which are more likely to have open-door admissions policies. More than two-thirds of first-time students enrolling in Arkansas’ community colleges needed remedial courses in 2014, for instance. About 60 percent of those in Massachusetts and Tennessee did.

But even four-year schools, which are more likely to have some admissions criteria, were not immune. In the California State University system, which admitted about 72 percent of first-time freshman applicants in 2014, more than 40 percent of incoming freshman were deemed not ready for college-level work in at least one subject. Nearly a quarter of incoming students at Colorado’s and Montana’s four-year schools were placed in remedial courses and about 30 percent were in Arkansas.

The University of Arkansas-Fort Smith needed to remediate 36 percent of its students in 2014. Students who score a 19 or better on the ACT are automatically enrolled in college-level courses. Those who do worse are either enrolled directly in a remedial class or take additional tests to determine their placement.

If students’ scores are too low, they can be admitted as non-degree seeking students for up to 15 credit hours to earn a certificate or work toward improving their score on a placement exam.

Officials say it wouldn’t be practical for a school like Fort Smith to mandate that all incoming students be ready to go into college algebra or English 101.

“We’re not a terribly populous state. Not everyone is going to go to college and we’ve got a fair number of colleges,” said Michael Moore, vice president of academic affairs for the University of Arkansas system. “Your enrollment will be tiny and you won’t be able to afford the faculty.”

Many college administrators also make an ethical argument for enrolling students who need remediation: It’s the college’s job to help make up for circumstances that have left students unprepared, not to punish them.

“College education has such a transformative power,” Moore said. “To simply tell people you’re not going to college because you qualify for remedial education, I think, would be wrong. That sort of places the blame on the student.”

Instead, many schools across the country are focusing on getting students ready for college-level work as efficiently as possible.

Some colleges, including BCCC, are partnering with local school districts to push remediation into high schools. BCCC has also pared down some of its remedial courses from 16 weeks to 12 or eight. They’re experimenting with different open source materials to decrease the cost of remedial textbooks and remove that financial hurdle for students.

At Fort Smith, a math professor has created an online math program, in which remedial students can go through different lessons at their own pace. The school (and many others in the Arkansas system) has also developed a co-requisite program, in which students enroll directly in college-level courses, but have an extra hour per class built in for remediation.

It’s similar to a model developed by the Community College of Baltimore County and now used by 254 schools across the country. In CCBC’s program, a professor teaches a session of college-level English 101 for an hour and fifteen minutes. Then, immediately afterward, students needing remediation (about half the class) spend an additional 75 minutes with the same instructor, honing in on problem areas. In 2014, nearly 40 percent of students in this program not only finished English 101 but went on to complete English 102, compared to fewer than 15 percent in traditional developmental courses, according to data from the college.

Programs and experiments like these take considerable time and energy — as well as more money than traditional remedial courses — for colleges to run. The Community College of Baltimore County program, for example, costs $78,000 a year for 54 credit hours; $35,000 of that is spent training faculty how to teach these courses, officials said. But CCBC President Kurtinitis says it’s worth it.

“It’s an expense we incur gladly,” she said. “It’s really an investment in retaining students who are now prepared at the college level.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Read more about higher education.

Originally published January 30th, 2017. Photo: Sarah Butrymowicz. Graphics: Nicole Lewis.

Sarah Butrymowicz

Sarah Butrymowicz is senior editor for investigations. For her first four years at The Hechinger Report, she was a staff writer, covering k-12 education.